Counter-Photography – Japan’s Artists Today

Sep 4–Oct 19, 2008

Image Gallery

-RESIZE.jpg)

-RESIZE.jpg)

Counter-Photography – Japan’s Artists Today

Sep 4–Oct 19, 2008

September 4 – October 19, 2008

Main Gallery

Curated by Yuri MITSUD, The Shoto Museum of Art

“Today we reveal the reality that is behind visible things”

Paul Klee

1.

When photography was invented 160 years ago, people marveled at its reproducibility. Painters declared that, today is the last day of painting, because they had admired the precise and unparalleled capability of photography to “copy the real.” Photography became the most effective method of documentation because of the camera’s ability to capture everything in front of the lens, and it was also recognized as the best proof of existences.

However, we tend to forget that when the documentary nature of photography was generally recognized, it also brought about a completely opposite reaction. This reaction created and amplified people’s aspiration to want “to capture,” “to win recognition of,” and “reveal” things that are not visible.

This opposite reaction can only be clearly understood if you recall the long history – almost as long as the history of photography itself — of such things as the psychic photos of ghosts and ectoplasm, the evidence photos of fairies, dinosaurs, UFOs, and ESP, as well as of the whole variety of trick photos. Since the very beginning, photography has been used as a means of fulfilling people’s desire so that they can capture things that are not visible. The great efforts put into the taking of photos for science of the infinitesimally small, genes and atomic levels, as well as of the vastly distant, as with the photos of nebulae tens of thousands of light-years away, are all connected to the fore-mentioned desires of people.

The quote at the beginning of this essay, are from the painter, P. Klee, in 1920. This is Klee’s definition of art. While Klee does not include photography in his definition, in my view, art naturally does in fact include “photography.” More relevant to this essay, however, is that Klee was one of the trailblazers of the style of abstract painting in Europe. The appearance of abstract painting, which was exceedingly modern and Western, and corresponded with the trend of the 20th century, is closely related to the proliferation of photography.

While painting used to monopolize the reproductive function before the advent of photography, it had no choice but to hand over this role to photography. This made it clear that the spiritual expression is what makes painting indispensable. Thus, it is an accepted theory in today’s art history that that was when abstract painting became one of the essential styles of art. It is no coincidence that the great abstract painters, like the Swedish artist, P. Klee, as well as the Russian artists, W. Kandinsky and K. Malevich, all created their works based on the exploration of their unknown internal world. Abstract expressions could not have been possible without the belief in this internal world.

However, today, as we approach the new century, abstract painting that was once a fertile expression, seems to have turned into a blind alley. Abstract painting that was based on the belief in the universal value of one’s internal world has been dismantled, individualized and sectionalized. At this point, I doubt whether there will still be the internal world necessary for the creation of fertile abstract expressions in the next century.

Photography, on the other hand, has rapidly proliferated in society, and has been in great demand due to its documenting and duplicating characteristics. This medium developed by constantly being conscious of the trends of painting that depicted the internal world. Whether the style was Victorian or Modern in technique, people in this field more or less shared the same point of view. What I am implying is not about the dichotomy of the very classical types of photography, which was the theme of the exhibition titled “Mirrors and Windows” held in New York in 1976. Rather, my point relates to the dynamic crisscross between painting and photography in the 20th century. This crisscross relationship ended at the turn of this century. In other words, photography has become one of the leading media in revealing things behind the visible.

This was possible because photography itself is not abstract, rather, it is an individual, an exclusive, and a specific medium. Although the basis of today’s world has been dismantled, photography can be created on the precondition that the world is baseless, because this medium can express things individually as fragments. Thus, photography can effectively search for the reality behind the visible through the lead of a single fragment.

There has been no other age than today when the value concealed behind the visible is required. In my point of view, this is the most important role photography should take in today’s world. With this in mind, I have selected eleven artists for this exhibition. Utilizing a camera, considered as an optical instrument, the artists have all succeeded in capturing the non-existent and the non-visible. These Japanese artists explore the “unseeable” strictly according to their own thoughts, without applying any retouches or tricks in the process of developing or printing photographs. I hope that each of you viewing this exhibition can share the sensations the artists are conveying based on their attitude to explore into the invisible existences.

2.

Needless to say, today’s electronic environment has created two opposing factors. Economically, the world has been reconstructed into a unitary market through globalization, which was supported by the United States. It seems that nobody can escape from this situation. This applies to the art market as well. From this point of view, we are all forced to be in one place. On the other hand, the proliferation of the Internet has made the mass media relative, and the information that can be obtained and sent out by individuals became unlimited. Although this state is making copyrights difficult to protect, culturally speaking, unprecedented pluralistic choices became possible. Counteractions of both the globalization and the proliferation of the Internet are occurring as well. The development of the unitary market has brought about the trend to form a local block-like economy, and the chaotic state of the excessive information is in demand of a full-scale indexing system.

Under such situation, it would not be realistic for photography to be confined to printing on silver-salt photographic paper. The fate of today’s photography is to continue being enlarged and reduced in size, transformed, and replaced, as well as to be sent out everywhere and to appear on every surface. Therefore, this exhibition also consists of works of various sizes, techniques, and materials. Regardless of the rapid changes, photography still possesses the exclusive and specific elements. This is also the fate of photography. Photography, like people today, exists in both the unitary and the pluralistic states.

Because photography is not a traditional medium, it has become a worldwide, common language, and can exist in the unitary state. However, it is also a fact that the individual work of artists cannot avoid being marked with his/her own uniqueness, even if it involves creating works contrary to the trend of the images captured through a lens that is having a hard time securing copyrights. This state is also connected to the above-mentioned “living in the unitary and pluralistic state.”

Some of you might think that what I have written so far does not concern the art in Japan because it is an island country in the Far East. Or you might expect this essay to go into the content of “to glorify Japonism,” focusing for instance on Ukiyoe’s flat and simplified expression becoming the source of modernist painting, as well as abstract painting. However, what I want to point out is that people living in Japan, like the rest of the world, have no choice but to witness the end of modernism. Therefore, it is a solemn truth that we must all accept the changes of the world, and search for something without having any mental guidelines we firmly believe in.

In Japan, the fifty years of economic growth have come to an end, and the value of every commodity drastically declined. As Japan experienced the state of economic declining in the international society, the Japanese not only realized how unsteady their own footing was when struck by the great earthquake, but was also shaken by the terrorists of a religious cult. However, these are all only superficial phenomena.

During the 150-year modern history in Japan, which is almost as long as the history of photography, Japan learned from the European world. Since their defeat in World War Two in 1945, the Japanese have put their sincere and enthusiastic effort into learning from mainly the United States. The same as not being able to imagine a world without photography, people in Japan can no longer imagine the purely, traditional, Japanese lifestyle that are excluded of every Western influence.

However, in the modernistic world of art, it is inevitable that Japanese artists should consider the meaning of being Japanese. This is similar to women artists having to continue pondering the meaning of being a woman in a male-dominated society. They also have no choice but to be placed under the pluralistic state and still live in the unitary world.

If Japanese people ask themselves, “What is the meaning of being a Japanese?” finding the answer inevitably takes a meandering course, but this is unavoidable considering their history. Women artists in the same situation continue to strive to express themselves in their own words. Therefore, even if the Japanese cannot avoid taking a meandering course, they have no choice but to express themselves in their own words, through translation, or by learning to speak English, which is the lingua franca of today.

In my opinion, photography has the potential to be utilized as a common language for Japanese to express themselves. In other words, photography is now a world language because, instead of remaining confined to the status of a traditional art, as it was in England and France where it was first invented, it has developed into a mechanical and chemical device of the modern era.

The main themes of the eleven artists I have selected for this exhibition are not directly related to “Japan,” however, they are all well aware that this subject cannot be ignored.

This exhibition consists of two sections. The first section is entitled “To Distill: Another Appearance,” and the second is entitled “To Reverse: Another Relationship.” Based on the idea, “to reveal the reality behind the visible,” the two sections show different approaches and themes.

The “To Distill – Another Appearance” shows the artists’ intention to explore the appearances of other dimensions, different from the conventional ones, by abstracting “the spirit,” which is the essence of things.

Animism is the belief in the existence of spirits in plants and stones. In my opinion, to exclude Animism because it is the most primitive religion is a biased modernistic view. However, I am not in favor of the extremely simple Animism that still exists in Japan today. Rather, I see encouraging possibilities in the artists’ intention to want to recognize and consider “things,” other than human beings, and which exist in different spheres outside the conventional. The “different spheres” hidden in “things” would, no doubt, be those antithetical to established conventions. Therefore, artists must go beyond the familiar appearance of “things,” and explore the different appearances that supposedly exist in the core. I entitled this section “To Distill” in order to describe the abstracting process mentioned above.

In my view, the “distillation” process, is a very current style, but we cannot ignore the fact that in Japan’s art history, prior to modern times, similar styles existed. Common elements can be found, for instance, in the high abstract of “Shoheiga” (painting on partitions, such as the sliding paper doors and folding screens) of the Edo era, as well as in Muromachi era “Suibokuga” (Indian ink drawings) that convey a sense of life through its ephemeral nature quite different from those created in China. The “distill” style might look similar to the paintings of Gerhard Richter, and to the way Christian Boltanski creates photographs. Even though similarities might be found in the works, the artists are no exception to the rule, and thus also live in the world that have the unitary and the pluralistic factors as well.

“The Reverse: Another Relationship,” shows a more social approach. While the “distill” style is more personal and sensuous, the subjects of which are “things,” in “The Reverse” the works depict realities through the process of translating and recomposing the relationship between people and society, and between one another. The subjects include “community” that is symbolic of “Japan,” and the relationship between the Self and the Other.

It is inevitable for the artists’ work containing reality to be far removed from realism, because one can never actually see through the eyes of the Other. There is no way for us to ever be certain of the world viewed by the Other. In my opinion, to be content with a work that depicts what comes into one’s sight, by using a simple one-point perspective, under the name of realism, is considered a mistake.

Therefore, the works shown in this exhibition are not documentary photographs that merely depict actual existences. Rather, the artists are exploring “the spirit” behind actual existences, so that they can find new realities and other ways for people to establish relationships with one another. Therefore, the artists create their works through their own experience of the day by day reality. Then they exhibit them after reversing and transforming the topology in their own approaches with the aim of presenting ways for us to reconsider the realities.

Today, when the long-established communities of every scale have become unstable, and all undergoing transformations, works that explore different ways of relating to society by transforming the topology, are unquestionably seriously in need, but the extent of difficulty involved is apparent as well.

When there was still the common sense of values necessary to establish a community, it was possible for us to criticize and to dismantle our community. However, in an age where everything needs to be reconsidered, there can be no easy, straight path we can take. At least, not until we can imagine the destination of our goal. Every one of us must accept the fact that there is no straight path to our future.

Therefore, even if you think you have found works that contain fantasy or that avoid the faces of the Other, please do not misinterpret them as works isolated from reality. For the artists have created their works based on their own specific encounters with reality, but have no intention of leading the viewers to any certain thought. Their style that reverse, transform and recompose each piece of their work in their own way, is a possible method for today, as well as a positive approach. Thus, the works are all sincere proposals for our future.

To once again reveal the realities we have left behind, and to create “Another Appearance” and “Another Relationship” in this age of chaos — worthy efforts necessary to realize these have already begun. With your understanding of this concept, I am confident that the significance of this exhibition will be clearly conveyed to you.

Commentaries on the Artists

1. “To Distill: Another Appearance”

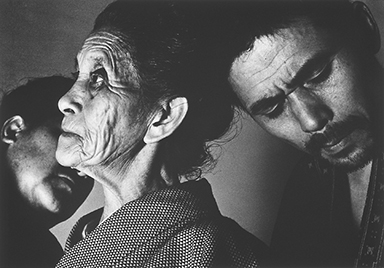

(1) Eikoh Hosoe

Eikoh Hosoe belongs to the first post-war generation of photography, working in this medium as an artist rather than as a photographer.

The bodies of men and women abstracted to the point of line drawings are the forms of the essence of life. The works are “distilled” to the very limit between existence and non-existence, and are emitting an aura.

While the nude photography in modernism was taken as a fragmental object that could be manipulated, Hosoe’s camera never captures the bodies from a dominant angle that would have any possibility of being manipulative. Therefore, the series of works in this exhibition are not merely expressing the bodies of the opposite sex, but are depicting the discovery of the equal and diverse relationships, such as the dialogue, the opposition, and the struggle between the masculine gender and the feminine gender.

(2) Miho Akioka

Miho Akioka’s camera lens focuses on the lively state of the life of a tree. The tree, coexisting with the wind, creates shadows by receiving light, and exists in the flow of time by touching every element of the external world – when the continuity of this is directly captured in her film, the image of the tree reaches another dimension of appearance than that of the phenomenal world. The image that appears through the process of transforming them into fine-grained colors on hemp paper, utilizing the New Enlarging Color Operation, gives the viewers the impression of an immaterial lightness that resembles the image of the spirit, at the same time, the spirit of the image.

(3) Miyuki Ichikawa

Miyuki Ichikawa places her camera against the lens of a pair of binoculars, and captures a ship sailing beyond the sunlight reflecting the surface of the ocean. Her eyes that look into the two discontinuous camera obscuras and lenses must go through the uncontrollable invasion of the external light. Her method that purposefully incorporates “the devices to see” as obstacles, not only dismantles the perspective method, but also expresses her strong aspiration to look at things that are difficult to see through her own eyes. The same feeling underlies in her other series of works that capture the uncertain condition of cloudy skies seen through a boundary fence.

(4) Hiroshi Sugimoto

The buildings seen in Hiroshi Sugimoto’s work are masculine monuments that originally possessed concrete forms. The solid buildings had taken shape through the creativity of builders and architects with the aim of showing the power and wealth that maintain civilization. However, Sugimoto excludes the solid materiality from well-known buildings, and shows an aggregate of shadows, which is similar to seeing a fleeting nightmare. Through the lens of his camera, Sugimoto’s nihilistic view succeeds in infusing poison into the glorious products of modernism, and in abstracting their illusory appearances and reversing their values. His architectural photography also achieves to exquisitely deny the materialistic nature possessed by objects.

(5) Akiko Sugiyama

The method Akiko Sugiyama recently utilizes is to create objects that are highly abstracted and to reduce them to only graphical elements. She then takes photographs of these objects. A set of these photos, taken after precisely calculating the lighting and angle, expresses the feeling a certain space can convey as we enter and walk inside a building. At first glance, the composition of her work looks very solid, but in substance, it approaches into very sensuous subjects such as how the human body exists, and how we feel about the external world. When viewing Sugiyama’s work, we are carried off from the confines of the conventional, cliched sensations, and evokes perceptions in us of the external world in a different way.

(6) Chie Yasuda

When Chie Yasuda travels, she stops to look at the obscure, abandoned corners of old botanical gardens and museums. She often notices things deteriorating within the enclosure of spaces, and plants expiring in the stagnant air between the overlapping leaves.

Yasuda’s photograph is pervaded with a unique sense of aura that has accumulated densely just in that particular space. She abstracts the particular time, and the smell that was in the air, as well as the realistic sensations one feels inside such spaces. She does not only not capture the substance of things, but is even trying to eliminate it. The work she has succeeded in creating is not only difficult but also requires extreme sensitivity and a radical state of mind.

2. “To Reverse: Another Relationship”

(1) Eikoh Hosoe, “A Weasel’s Slash”

The works are the photographs that resulted from the collaboration between Eikoh Hosoe and Tatsumi Hijikata, the originator of Butoh, which took place when they traveled to Hijikata’s hometown in Akita. Hijikata, an odd-looking, unique dancer, visiting his hometown, spent time with the people living on farms. The encounters between the completely heterogeneous natures sparked the Butoh dancer. Hosoe captures the essence of Hijikata’s performance, as well as the scenes peculiar to that land. Hosoe’s work lies somewhere between documentary and fantasy. The photographs are his tragicomical effort to reverse the relationship between the local residents and Hijikata, which can never be possible.

(2) Kazuo Katase, “Behind the Light”

Kazuo Katase lived in Germany for almost thirty years. When he came back to Japan after a long absence, he took a new look at his country with a feeling of incongruity. Retracing the source of his incongruous feeling meant retracing his own self. The subjects of his work are, the gate of Ise Shrine (Japan’s head Shinto shrine), the sacred Mount Fuji (the highest peak in Japan), and a tea ceremony bowl that signifies the soul of Zen. He displays the works by printing the reversed image of a photograph, and when the three works are installed together, the amalgam of the Emperor system, animism and Buddhism manifests. In reality, these subjects are being left behind in our daily lives, and that is why he is questioning the depth of recognition of these subjects, and the extent of their omnipresence in Japan.

(3) Hiroko Inoue, “Absence”

Hiroko Inoue took a collection of photographs of the outside world as viewed through the windows from the inside of mental institutions. Most of the works are of iron-barred windows. She collected the images as she traveled and talked to the staff and patients of each mental institution she visited. She explained the reason for taking the photographs and persuaded them to give her permission. Her aim is not to create the typical visual world of people who live in confinement due to their sicknesses. Rather, she recomposes the scene viewed from the window – normally seen by the patients — through her own eyes. Therefore, after the process of printing the images directly on cloths, the windows which appear on light-boxes, are not the windows viewed by the Other but are those viewed with her own eyes. Her work is similar to having a dialogue with the Other’s visual world, but also contains the artist’s memory and physical nature.

(4) Tomoko Yoneda, “topological analogy”

Tomoko Yoneda takes photographs of the wallpaper of a room after the resident has moved out. In the empty room, she retraces the past time of the former resident. The wallpaper acts as the phase of the border in order to be led to retrace the time. Nothing specific about the former resident can actually be perceived from her photographs, such as the documentation on his/her life in the room, physical existence and thoughts. In other words, she excludes the substantial elements normally found in a person. What is important for the artist is the fact that a certain period of time had accumulated in the space. Her work tells the story that the accumulations of time had steadily been stored in different rooms, and that a room exists in parallel with other rooms, and all in a similar fashion. The viewers are led to realize that what they feel from her work is the essence of existences.

(5) Tomoaki Ishihara

The self-portrait of Tomoaki Ishihara is the manifestation of his attitude toward his own self. Ishihara chose art museums as the background for his portrait. He turns his back to the paintings that are on display. The camera lens that passes by the artist, yelling and meditating toward the lens, focuses on the paintings on the wall. In his work, the relationship between him and the background is constructed through the multi-layer “to see/to be seen” paradox. In the photo, his face that blocks the view, in front of the paintings, resembles a blurred heterogeneous object. In the humorous power struggle, between himself and the background, Ishihara’s self-portrait is torn in two. That is, he captures himself as a part of the entire scene that is viewed, analyzed and exposed. At the same time, he captures himself standing in the way of the lens as if he were the soloist in the scene.

(6) Michihiro Shimabuku “Searching for Deer”

Michihiro Shimabuku decides to look for “deer” in a country town that is not even in the woodlands. As he rides on his bicycle, flowers planted in the basket of his bicycle, he continues to ask people about the “deer.” He encounters many “deer” as he had anticipated. His work is in between fantasy and documentary. Godot was only being waited for, but the “deer” was actually found.

The substance of his work is the fascinating sensation the viewers feel from the search for the “deer,” that gradually unfolds through the encounters and exchanges with people. The essence of his work is found in the magical method of the artist who begins from scratch and develops his relationships with unknown people, and creates a formless work from the relationships he has made. Therefore, the photographs and the texts are considered the evidence of “something” that had existed.